Illustrations : Sylvain Rivard

WATER DRUM (kanatio :iàword from Mohawk language

Among Iroquoian peoples, the traditional water drum is small in size and cylindrical. A few centimetres of water are poured into a cedar (Thuja occidentalis) or linden (Tilia glabra) barrel to moisten and tighten the drum skin. The latter is usually made from deerhide (Odocoileus virginianus), attached with a ring made of wood and leather. This process makes the sound more elastic. Continuous beating of this type of drum with a sculpted stick, sometimes curved, accompanies most social songs.

Among Iroquoian peoples, the traditional water drum is small in size and cylindrical. A few centimetres of water are poured into a cedar (Thuja occidentalis) or linden (Tilia glabra) barrel to moisten and tighten the drum skin. The latter is usually made from deerhide (Odocoileus virginianus), attached with a ring made of wood and leather. This process makes the sound more elastic. Continuous beating of this type of drum with a sculpted stick, sometimes curved, accompanies most social songs.

The water drum, used by men, was designed to be played within the longhouse, the traditional Iroquoian dwelling also used as a place of worship. Thus, its sound dœs not carry as far as Algonquian-style drums.

DRUM (teueikan) word from Innu language

The songs and dances of nations in the great Algonquian family are usually accompanied by drums of different shapes and sizes Some are shaped from a single cervid skin stretched over a wooden frame with a gut handle on the back, while others, less common, are double, with the handle at the top of the frame. In the Innu version, a Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) tendon, with interwoven porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) quills, crosses the side the skin membrane is mounted on. These quills are a kind of snare giving the drum a particular sound quality. Most drum frames are round, but there is also an octagonal shape. For Algonquian peoples, the drum is above all a ritual object. Thus, it is not rare to see it embellished with symbolic designs and images as well as medicinal objects hung around its frame.

The songs and dances of nations in the great Algonquian family are usually accompanied by drums of different shapes and sizes Some are shaped from a single cervid skin stretched over a wooden frame with a gut handle on the back, while others, less common, are double, with the handle at the top of the frame. In the Innu version, a Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) tendon, with interwoven porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) quills, crosses the side the skin membrane is mounted on. These quills are a kind of snare giving the drum a particular sound quality. Most drum frames are round, but there is also an octagonal shape. For Algonquian peoples, the drum is above all a ritual object. Thus, it is not rare to see it embellished with symbolic designs and images as well as medicinal objects hung around its frame.

GREAT DRUM (mistikwaskihk) word from the Cree language

This impressive drum originates in regions to the west of the Great Lakes. The gradual expansion of the Powwow movement is responsible for its introduction to Northeastern North America. Approximately 1 metre in diameter, the wooden frame with one face covered by stretched buffalo hide is suspended from cross-shaped wooden bars to give it greater resonance. Long beaters with various tips are used by the four to eight people making up the group of musicians/singers who play this type of drum.

TURTLE RATTLE (Anowara ohsta:wà) word from the Mohawk language

Rare object exclusively used in Iroquoian rituals, made from the body of the snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina serpentina). The turtle’s body is removed from its shell, and the shell’s openings are sewn shut after inserting pebbles or corn kernels. The head, with the neck stretched out over a wooden stick, is used as the handle. This rattle, with a sound varying according to its size, is played by a chosen singer who shakes it or strikes it on any available solid surface.

Rare object exclusively used in Iroquoian rituals, made from the body of the snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina serpentina). The turtle’s body is removed from its shell, and the shell’s openings are sewn shut after inserting pebbles or corn kernels. The head, with the neck stretched out over a wooden stick, is used as the handle. This rattle, with a sound varying according to its size, is played by a chosen singer who shakes it or strikes it on any available solid surface.

BARK RATTLE (Pezagholiganisisiwan) word from the Abenaki language

One type of Iroquoian rattle is made from Elm (Ulmus americana) bark. A piece of bark the length of an arm and approximately 15 cm wide is harvested from the tree and folded in half. Pebbles, corn kernels or fruit pits are inserted in the envelope and the bark is then folded in at its opening and attached with straps of animal or vegetable origin. This type is almost never made any more, because the elm has become an increasingly rare species in North America.

One type of Iroquoian rattle is made from Elm (Ulmus americana) bark. A piece of bark the length of an arm and approximately 15 cm wide is harvested from the tree and folded in half. Pebbles, corn kernels or fruit pits are inserted in the envelope and the bark is then folded in at its opening and attached with straps of animal or vegetable origin. This type is almost never made any more, because the elm has become an increasingly rare species in North America.

HORN RATTLE (Halonossis) word from the Malachite language

![]() Rattles made from buffalo (Bison bison) or domestic cattle horn are made and used by the Iroquoians. The Abenakis also use them. The hollowed-out horn is filled with pebbles and closed off at both ends by wooden plugs. The wooden handle is lightly sculpted to provide a better grip. The constant rustling sound is obtained by striking the rattle against the thigh if seated or the palm of the hand if standing.

Rattles made from buffalo (Bison bison) or domestic cattle horn are made and used by the Iroquoians. The Abenakis also use them. The hollowed-out horn is filled with pebbles and closed off at both ends by wooden plugs. The wooden handle is lightly sculpted to provide a better grip. The constant rustling sound is obtained by striking the rattle against the thigh if seated or the palm of the hand if standing.

SQUASH RATTLE (wasawaisisiwan) word from the Abenaki language

![]() Some types of small squashes and the calabash are used by farming peoples to make rattles. These are dried, then hollowed out and finally filled with a handful of corn kernels, glass beads or fruit pits and finally fitted with a wooden handle, often adorned with incisions, beads and feathers. This common instrument is used throughout the Americas and known by the generic name maracas (word from the Tupi-Guarani language) in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Some types of small squashes and the calabash are used by farming peoples to make rattles. These are dried, then hollowed out and finally filled with a handful of corn kernels, glass beads or fruit pits and finally fitted with a wooden handle, often adorned with incisions, beads and feathers. This common instrument is used throughout the Americas and known by the generic name maracas (word from the Tupi-Guarani language) in Latin America and the Caribbean.

BELLS (Sokwahiganal) word from the Abenaki language

Leather or fabric garters holding dancers’ deerskin leggings in place are often adorned with cervid hooves. These hooves, arranged in dangles, make a jingling sound when they strike against one another with the dancers’ steps. This ancient instrument is called “Dodogezawas” in the Abenaki language. Since contact between Europeans and Aboriginal Americans, small bells made of tin, copper or other metals were gradually introduced into the material culture of peoples of the Americas. They were quickly adopted to adorn articles of dress. The metal bells that now adorn Powwow dancers’ ankles derive from this ancient custom.

Leather or fabric garters holding dancers’ deerskin leggings in place are often adorned with cervid hooves. These hooves, arranged in dangles, make a jingling sound when they strike against one another with the dancers’ steps. This ancient instrument is called “Dodogezawas” in the Abenaki language. Since contact between Europeans and Aboriginal Americans, small bells made of tin, copper or other metals were gradually introduced into the material culture of peoples of the Americas. They were quickly adopted to adorn articles of dress. The metal bells that now adorn Powwow dancers’ ankles derive from this ancient custom.

FLUTE (Pikw8gan) word from the Abenaki language

The flute and the whistle were the only melodic instruments formerly in use among North American First Nations. These instruments were made from different materials, including reeds, clay, wood and bone.

The flute and the whistle were the only melodic instruments formerly in use among North American First Nations. These instruments were made from different materials, including reeds, clay, wood and bone.

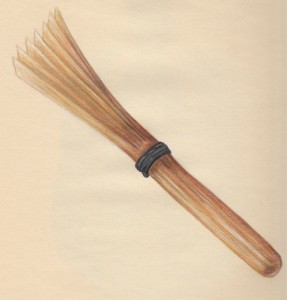

CLAPPER (Ji’gmaquan or Elaskate’kn) words from Micmac language

Contrary to the other nations, the Micmacs used a simpler form of percussion instrument to back up their dances and songs. The oldest form is a piece of birchbark (Betula papyrifera) folded back several times and struck with a stick. This instrument was often used instead of a drum. The most particular Micmac instrument is a clapper made from a stick of beech (Fraxinus nigra) approximately 35 cm, folded in half in several strips. Striking the raised side against the palm of the hand causes the vibrating sound. Artisans at the Listuguj community in Quebec and Eskasoni in Cape Breton still make this type of instrument.

Contrary to the other nations, the Micmacs used a simpler form of percussion instrument to back up their dances and songs. The oldest form is a piece of birchbark (Betula papyrifera) folded back several times and struck with a stick. This instrument was often used instead of a drum. The most particular Micmac instrument is a clapper made from a stick of beech (Fraxinus nigra) approximately 35 cm, folded in half in several strips. Striking the raised side against the palm of the hand causes the vibrating sound. Artisans at the Listuguj community in Quebec and Eskasoni in Cape Breton still make this type of instrument.